Strong Through the Shift: Vegan Nutrition for Perimenopause

/Lately, many of my friends and generally women around my age are talking more about perimenopause. While I'm yet to experience significant symptoms, I'm proactively preparing, researching and adjusting. Some of the changes I made is to my exercise routine and the amount of protein I consume daily. Another thing I try to be mindful of, especially after workouts, is getting enough leucine in my post-exercise meal or protein shake (depending on the time of day I train).

In this blog post, I’ll discuss protein intake during perimenopause and explain why leucine is important, as well as why excessive intake can carry risks. I’ll also share a few of my go-to breakfast, lunch, and dinner ideas that help ensure I’m getting enough protein, including leucine, after training.

Protein Intake in Perimenopause

There is a lot of advice out there concerning perimenopausal nutrition, but one thing is for sure: women in perimenopause and postmenopause require more protein, especially if they are highly active. This is because estrogen levels decline, which affects muscle maintenance, bone health, and metabolic function. Adequate protein intake helps support muscle mass, which becomes harder to preserve as we age, and it also plays a role in satiety and blood sugar stability, which can become more difficult to manage during this stage.

However, there is also evidence that too much protein, particularly from leucine-rich or highly concentrated sources, may activate pathways involved in atherosclerosis. While this research is still developing, and much of it comes from animal studies or short-term human trials, it suggests that chronically overloading on protein, especially in isolated forms, might carry cardiovascular risks. Diets high in protein but low in fibre can also negatively affect the gut microbiome, and some studies suggest a connection between elevated BCAAs and insulin resistance.

These risks seem lower when protein comes from plant-based sources, and when overall intake stays within a balanced range. Depending on activity levels as well as where you are in the life cycle, 0.8 to 1.4 grams per kilogram of body weight per day is likely safe, effective, and sustainable.

Because of this, I choose to stay on the side of caution. While many fitness-focused nutritionists may advocate much higher intakes per kilogram of body weight, they might be biased towards the needs of athletes or focused primarily on muscle building or performance, potentially overlooking long-term health concerns such as cardiovascular risk, kidney strain and insulin resistance. Currently, I feel my best when I aim for around 1.2 grams of protein per kilogram of body weight, which works out to about 70 grams of protein on training days, and a bit less (around 50 to 60 grams) on rest days. That’s a small but noticeable shift from my usual 45 to 50 grams per day, and it feels sustainable, nourishing, and aligned with my current lifestyle.

What is Leucine, Why Does It Matter, and Why Does the Dose Matter?

Leucine is one of the nine essential amino acids – the ones our bodies cannot produce on their own, so we have to get them through food. It is also one of the three branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs), which are especially important for muscle maintenance and recovery. What makes leucine stand out is its role as a kind of metabolic trigger. It plays a key role in activating muscle protein synthesis, the process our body uses to repair and build muscle after exercise. Without enough leucine in a meal, even if you're eating plenty of protein overall, your body might not fully switch into rebuild mode.

However, recent research has raised concerns about the potential link between excessive protein intake, especially from leucine-rich sources, and the development of atherosclerosis. While protein is essential for muscle health, very high intakes (particularly over 25 grams per meal or more than 22 per cent of daily calories) may overstimulate the mTOR pathway in immune cells, contributing to the build-up of arterial plaque. Leucine appears to play a central role in this process.

In addition, several studies have linked elevated levels of BCAAs, including leucine, to insulin resistance and an increased risk of type 2 diabetes. High plasma BCAAs have been shown to disrupt insulin signalling and are associated with long-term metabolic dysfunction in some populations. While the research is ongoing, it suggests that consistently high intakes of leucine, particularly from concentrated animal or supplement sources, may not be without risk. Altogether, this highlights the importance of moderation, especially when using protein supplements, and supports the case for focusing on plant-based proteins, which tend to be lower in leucine and gentler on both cardiovascular and metabolic health.

Most research suggests that around 2.5 to 3 grams of leucine per meal is ideal for stimulating muscle protein synthesis, often referred to as the 'leucine threshold'. Exceeding this amount does not appear to offer additional benefits for muscle repair and may overstimulate metabolic pathways, such as mTOR, which have been linkedto atherosclerosis and insulin resistance in recent studies. While there is no official upper limit, a cautious approach would be to keep leucine intake per meal at or below 3 grams, and aim for a total of around 6 to 9 grams per day, ideally from whole food sources rather than concentrated protein supplements. A word of warning: A typical Western diet, or high-protein regimen with supplements, can easily push leucine intake above these levels.

To summarise, leucine plays a key role in supporting muscle repair and maintenance, especially as we age. However, like many things in nutrition, more is not always better. While it is essential to get enough leucine to support muscle protein synthesis, consistently exceeding the recommended amounts may carry long-term health risks. In short, leucine is beneficial, but too much of it may do more harm than good. As with most things, balance is key.

What I Eat for High Protein and Post-Exercise Leucine

Below is a list of different combinations I use to reach my protein and leucine targets after exercising. Sometimes I work out before breakfast (not fasted, as I usually have something small, most often coffee with homemade cashew or almond milk and an energy ball or two), other times before lunch, and occasionally in the mid-afternoon. If I exercise in the afternoon, I usually have a protein smoothie within 30 minutes afterwards. Otherwise, I follow up with breakfast or lunch.

Protein Powder Smoothies

Most plant-based protein powders are designed to provide around 20 to 25 grams of protein per serving, which is generally enough to support muscle recovery and reach the leucine threshold needed to stimulate muscle protein synthesis. However, this depends on the brand and the type of protein used. Powders made from soy or pea protein are particularly effective, as they are naturally higher in leucine. Many blends combine pea, soy, and sometimes hemp protein, and a single serving of these mixed powders will usually contain between 2.2 and 2.8 grams of leucine, which is enough to support muscle repair, especially after exercise. If the leucine content is not listed on the label, looking for a serving that provides at least 25 grams of protein from soy or pea is usually a reliable guide. I like to buy local, so I use Iswari (PT brand) protein powders, which are made with vegan and organic ingredients. I use their Super Vegan Protein, which is based on pea and pumpkin seed protein. I usually blend it with a banana, some blueberries, and occasionally a tablespoon of hemp seeds to boost the leucine content to 2.5 grams.

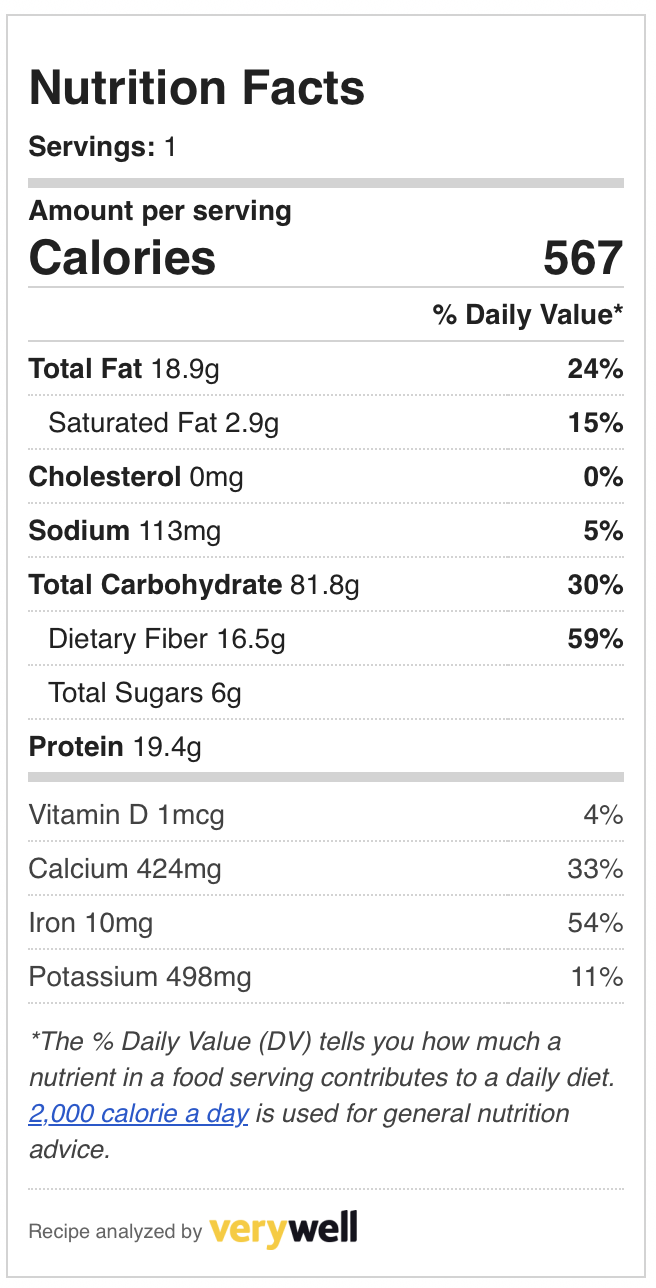

Breakfast Bowl (summer version)

Ingredients:

150g unsweetened soy yoghurt

½ scoop vegan pea protein powder

1 tbsp chia seeds (~12g)

1 tbsp hemp seeds (~10g)

1 tbsp pumpkin seeds (~10g)

30g granola or muesli

50g blueberries (fresh or frozen)

Protein: ~25.5 g

Leucine: ~2.5 g

Calories: ~350–370 kcal

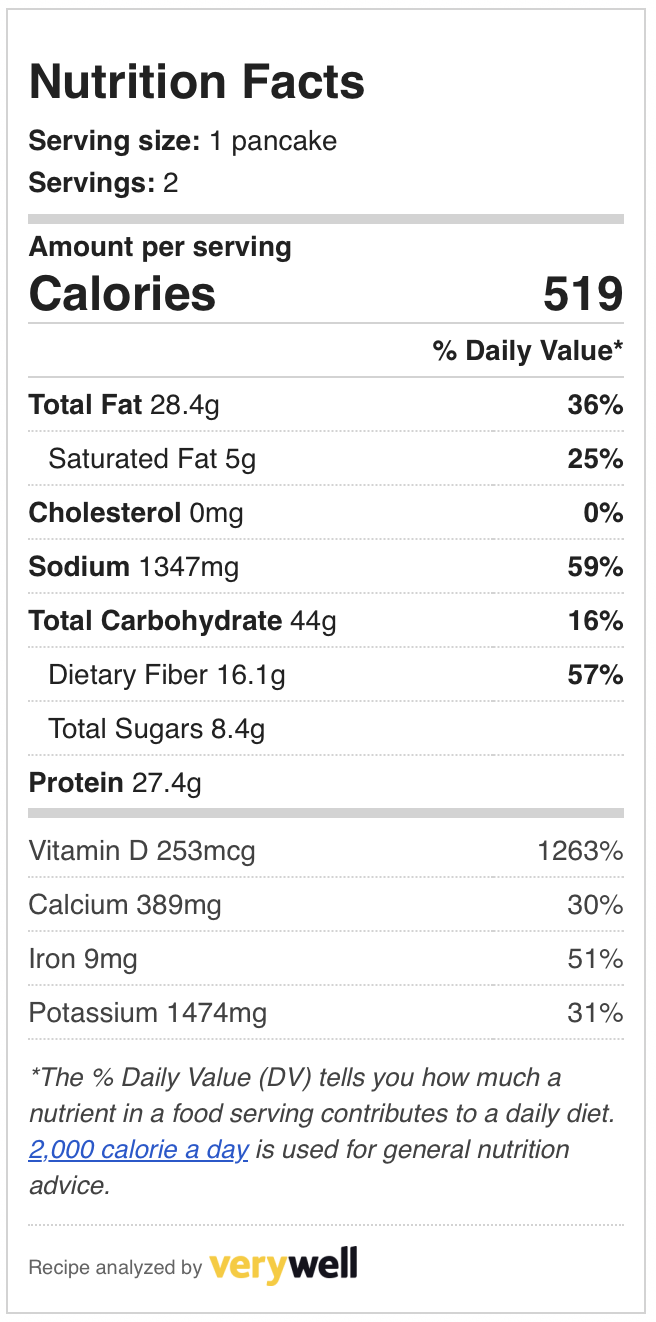

Tempeh Power Bowl (lunch idea)

Ingredients:

100g tempeh

½ cup cooked quinoa (90g)

1 tbsp hemp seeds (10g)

1 cup steamed broccoli

1 tbsp tahini or olive oil (optional)

Protein: ~29 g

Leucine: ~2.1–2.3 g

Calories: ~450–500 kcal (depending on oil/seeds)

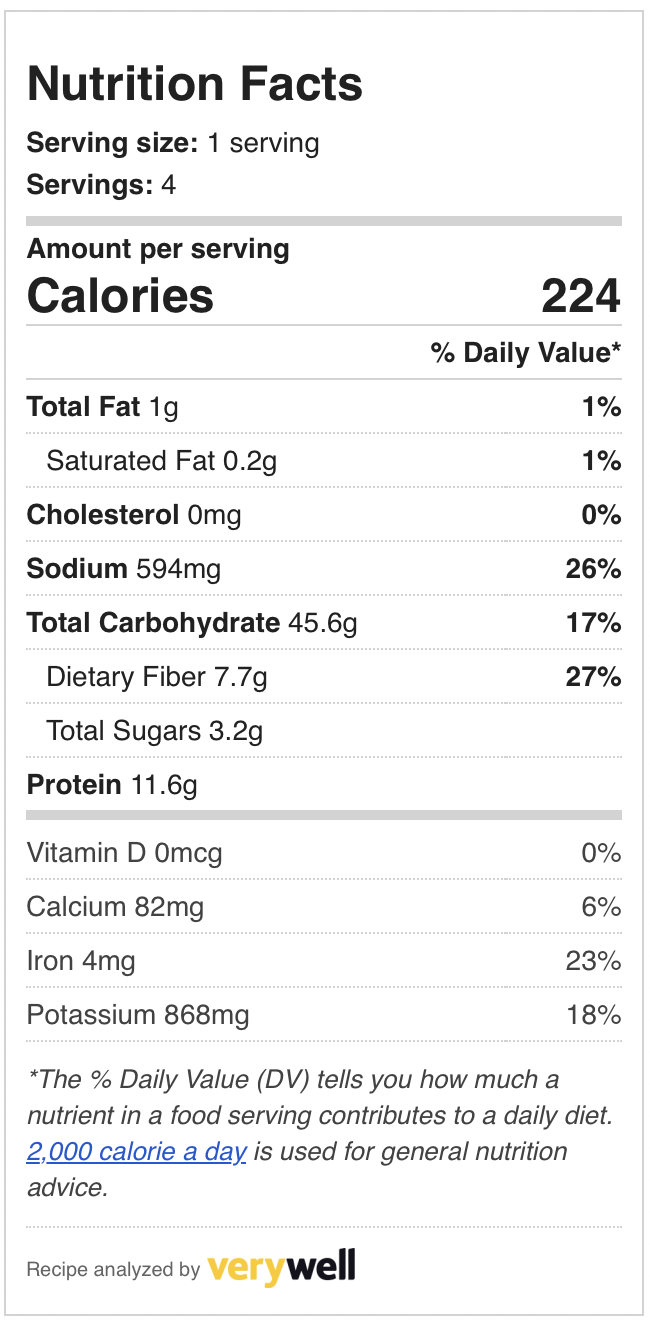

Tofu Stir-Fry with Rice (dinner idea)

150g firm tofu

½ cup cooked brown rice (or another grain) (100g)

1 tbsp pumpkin seeds (10g)

1 cup mixed stir-fried vegetables (e.g. bell pepper, bok choy, carrots, asparagus, broccoli)

1 tsp sesame oil + soy sauce, garlic, ginger

1 tbsp nutritional yeast

Protein: ~27–28 g

Leucine: ~2.0–2.3 g

Calories: ~450–480 kcal

Final Thoughts

Navigating perimenopause can feel like entering a new and unfamiliar phase of life, but it’s also an opportunity to deepen our connection with our bodies, our needs, and the rhythms that sustain us. For me, one of the most empowering shifts has been learning how to better support my strength, energy, and recovery with mindful exercise routines and thoughtful, plant-based nutrition. By approaching nutrition one meal at a time, with curiosity and care, we can meet the demands of this life stage while honouring long-term wellbeing. Whether you're plant-based or just plant-curious, I hope the ideas I’ve shared help you feel more confident in crafting meals that nourish your body, support your training, and set you up for strength, in every sense of the word.

References:

Lu, J., Xie, G., Jia, W., & Jia, W. (2013). Insulin resistance and the metabolism of branched-chain amino acids. Frontiers of medicine, 7(1), 53-59.

Wilkinson, K., Koscien, C. P., Monteyne, A. J., Wall, B. T., & Stephens, F. B. (2023). Association of postprandial postexercise muscle protein synthesis rates with dietary leucine: A systematic review. Physiological reports, 11(15), e15775.

Yoon, M. S. (2016). The emerging role of branched-chain amino acids in insulin resistance and metabolism. Nutrients, 8(7), 405.

Zhang, X., Kapoor, D., Jeong, S. J., Fappi, A., Stitham, J., Shabrish, V., ... & Razani, B. (2024). Identification of a leucine-mediated threshold effect governing macrophage mTOR signalling and cardiovascular risk. Nature metabolism, 6(2), 359-377.